Everyone in Ferria knew not to go out after dark.

When it was dark, the streets belonged to the monster.

Every day was filled with light. Filled with the sounds of delight and entertainment, and the lively noises of village life. The hammering of the forge, the tilling of the fields, the soft sounds of spinning and weaving. The gentle murmur of the marketplace, and raucous laughter from the inn. Music and games, dances and village meetings – all the things that brought joy to the heart of the villagers.

But everyone in Ferria knew not to go out after dark.

When the sun began to set, the people would close down their market stalls, put away their work, douse the forges, and wave goodnight to their neighbours. They carried in their crops, put their livestock in their shelters, and lit their lanterns with as much cheer as they went about the rest of their day. Candles would light the windows of every house, while outside grew quiet and still. You might think that they would scurry home in the last light of day, wary and afraid. But you would be wrong.

Because everyone in Ferria knew not to go out after dark.

Sometimes the children would wake in the night to a sound by their window. Perhaps rasping breathing, or low growls. Perhaps thudding footsteps or the dragging of something big and heavy. Perhaps the rough vibrations of something large rubbing against their wall. The youngest children would race to their parent’s beds, and leap under the covers in fear. Their parents would wake, bleary-eyed, and hold them close, whispering gentle comfort as they embraced them. “Do not worry, sweet little one, it’s just the monster. We’re safe, it’s alright.”

Sometimes adults who stayed up late, reading by candlelight, or playing games with dice and cards would pause at those same sounds, glance at their windows for a moment, then chuckle. “Just the monster taking a turn around the garden,” they would say to each other, before the rattling of dice and the soft conversation filled the room again.

You see, everyone in Ferria knew not to go out after dark.

In the morning, they would rouse slowly from their sweet dreams, rising alone or in families to begin the day anew. They brushed their hair, dressed themselves, and those too young or old to dress themselves, then got back to doing what brought them the joys of living. Cattle were returned to the field, mooing their delight at the clouds. The shepherds went out into the fields to count their flock and seek out any who had wandered. Wolves never took any of the animals the villagers relied upon, even the sheep that slept out on the hillside like clumps of mist clinging to the grass.

After all, everyone in Ferria knew not to go out after dark.

No wolves ever troubled the sheep, no bears bothered the villagers who foraged in the woods, and no bandits were to be found for miles around the little village nestled comfortably in the hills. Most of the villagers thought little of this, not knowing much of life beyond the peaceful countryside. Occasionally someone would pass through and remark at the absence of such troubles.

Someone would always reply, “Well, that’s because everyone in Ferria knows not to go out after dark.”

From time to time, a youth would take a trip to the big city. An adventure to learn new skills, to see new sights, to meet new people. When they returned from these trips they might ask why it was that the world beyond was so rife with struggles very unlike those the village experienced. The elders of the village would smile and ask them if the people in the city knew not to go out after dark.

Some of those young people were unhappy with this reply, though. They knew there was more to it than that, and perhaps they didn’t pick up on what was really being said. So the elders would sit them down and explain, always patiently, always kindly. They would tell their young friends, in soft voices and plain words, that the monster kept them safe. Yes, that same monster that their parents had told them about as children, and who could still be heard roving the streets to this day. Yes, the monster no-one ever talked about, not really, because what was there to say?

No, one-one ever seemed to be able to agree what it looked like, or how it sounded. No, no-one knew where it lived or what it did during the day. No, they didn’t want the curious youngster to try finding anything else out about it. Calm down, drink your ale, eat your sandwich, and take a moment to really think it through.

Because all the people of Ferria really needed to know was not to go out after dark.

So, no brigands or great beasts troubled the villagers. But every now and then, they would have to deal with a hero.

Heroes would turn up, usually alone, sometimes with little parties of followers and helpers. The most unbearable were the knights, with their fancy horses, silly armour, and squires racing to tend to their every whim. The villagers would roll their eyes at their approach, and argue about who should deal with the newcomer. Eventually one of the more robust villagers would find themselves volunteering, or volunteered, to greet the strange band of clanking people, or the lone, grizzled figure carrying too many weapons to be practical.

All of these heroes came for one reason. After all, Ferria wasn’t on the way to anywhere important, or famed for any particularly skilled workers or sages that might be worth making the trip for. Every single hero came to slay their monster.

They all wanted to know where the monster could be found; but there was no answer to that. They all wanted to know who it’s last victim was; but there was no answer to that. They all wanted to know what kind of beast it was; but there was no answer to that either. So many questions, always without answer. Almost all of the heroes would be angered by this, and go off to sulk and brood before nightfall would bring out the monster.

Very, very occasionally, though, a hero would listen and be curious. They would ask more questions, carefully, cautiously. They would seek out the elders and ask them yet more questions – or the same questions, just to be sure the answers were the same. And they would leave well before nightfall, or spend the night at the inn before heading home the next morning.

Because after speaking to the people of Ferria, they knew not to go out after dark.

But usually, the villagers didn’t get to relax and sigh out their relief. Instead the hero would set themselves up in the marketplace, being dutifully ignored by all the people working their stalls, or buying their fresh food and hand-crafted wares. The people would pack up at the end of the day, as the sun lowered in the sky, occasionally glancing at the shining knight or grubby mercenary who waited for the sunset. They would scurry home, no-one wanting to talk to the stranger who had set their mind on violence.

If the hero had been polite and kind, perhaps someone might pause on their way home and try one last time, inviting the fighter to stay with them, to stay safe and not invite the trouble they were seeking. That never worked, but sometimes someone felt they had to try. But then they would head home alone and behind dozens of locked doors the villagers would rest uneasily in their beds. No games would be played, no books read by candlelight. They spoke quietly to each other, and reassured their families that it would all be ok by morning.

On those days especially, everyone in Ferria knew not to go out after dark.

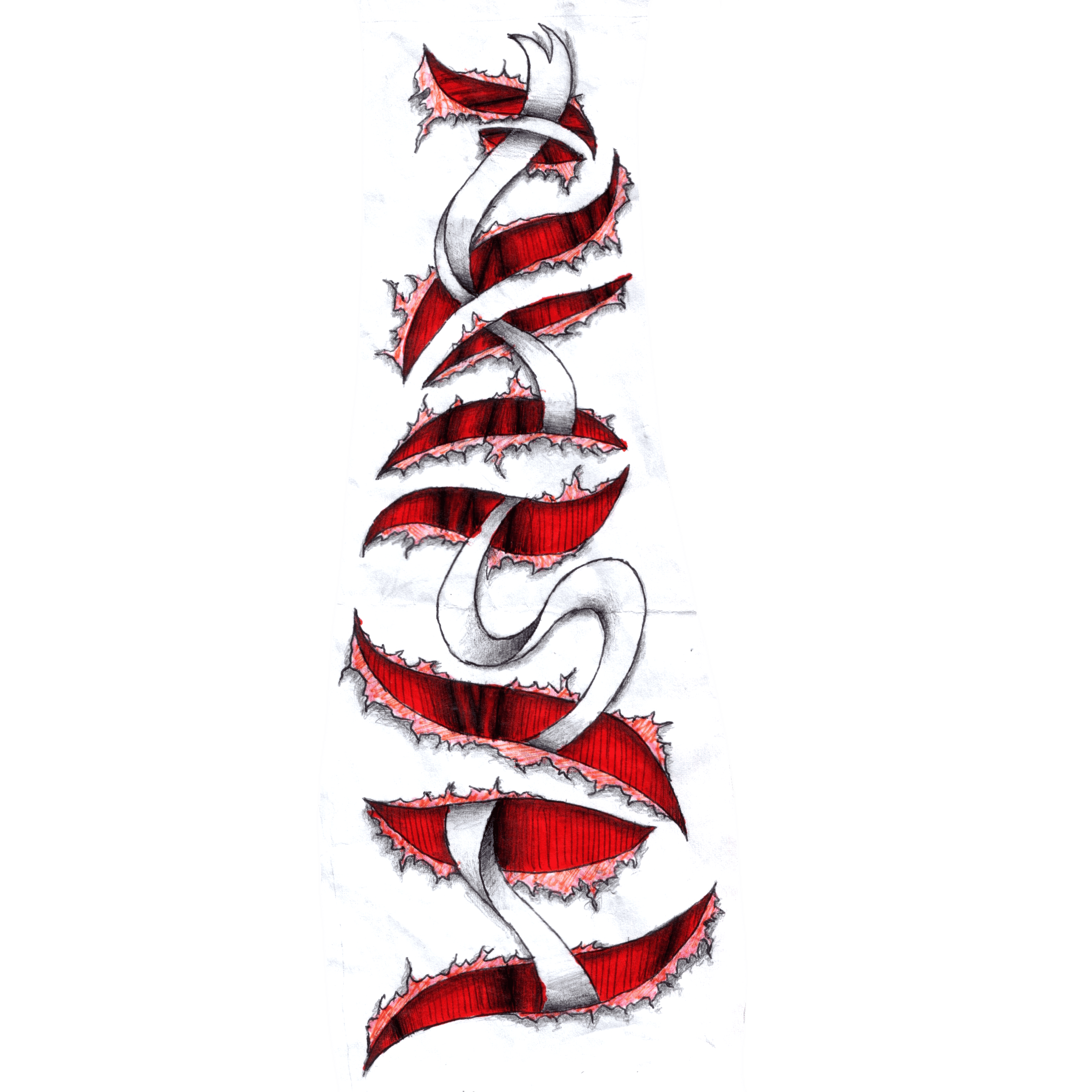

They might catch sounds of battle through their latched windows and closed shutters. More children than usual might rush to their parents beds, to have hands held over their ears and be rocked back to sleep. There was the bang and clatter of blades, the crash of heavy things hitting fences and walls, the screams of pain in human and inhuman tongues. No-one in Ferria would sleep well that night.

So when morning came, they would rise sleepily from their beds. One by one doors would open, and faces peer out cautiously. Then doors would shut again, one by one. Eventually, someone steps outside with a bucket, mop, apron and gloves, to begin the morning’s work. The scattered body parts and scraps of armour were picked up, one at a time, and dropped into the bucket. Someone else would join the work after a while, perhaps after the most gruesome scraps were dealt with. Weapons were found in bushes, tattered strips of clothing stained with blood pulled off walls and out of trees, and the pools of blood were mopped up, buried, or turned over into the mud. It never took as long as it seemed it should, and soon enough the rest of the villagers would come outside to fix fences, patch up walls, and set up the market stalls for the day.

A few of the people of Ferria would gather together the remains of the ill-fated heroes, and take them to the graveyard behind the village. A hole would be made in the soft dirt, which accepted the buckets of flesh with ease. Dirt was piled back in, but no headstone placed atop it. Someone might say a few words if the hero had seemed at least passingly pleasant to the villagers, and perhaps a tear or two were shed by the young, who had not seen this happen before. Then they would depart together, go home to clean themselves up, and get back to living the life they always had.

After those kinds of days, the villagers may haggle more grumpily over prices in the market. They might argue over little things with their neighbours, and be sterner with their children. The sadness and frustration at the senseless waste of life, and the disruption to their happy lives, had to come out somewhere, after all. Some people would drink a little more in the inn that day.

These weren’t the only days when someone would drink a little too much, of course. Perhaps a child had gone to town and their parents drowned their sadness at missing them, after a while. Perhaps a heart was broken, young or old, and they wept into their cups despite the comfort offered by their friends. Maybe a wedding was followed by raucous revelry, and one of the party supped a little too deeply on the celebratory wine.

On days like these, the intoxicated were mostly helped home by their fellows. But sometimes the drunkard would refuse to go home before dark. Or perhaps they insisted they were fine, only to be turned around in their stupor, wandering the streets mumbling and stumbling as the sun dropped below the horizon. The lights from shuttered windows casting just enough light to make the familiar roads unfamiliar to the addled mind, and confusing the wayward villager. Sometimes the inebriated soul would sit atop a wall, or plant themselves in the street, drink still in hand, obliviously singing to themselves as the light faded. Maybe they would stamp about, ranting at nothing, angry at the world, until they fell onto the cobbles. Eventually, they always fell asleep somewhere, the slumber taking away their sorrow, their anger or their joy.

The next morning, their neighbours would wake as usual, and step outside to smile in the morning sun. Glancing to the next house along the road, they may sigh, and head over carefully – stepping over the drag marks in their garden, and pushing open the unlocked door. They always carefully ignored the scratches on the doorposts, and the claw marks in the hallway floor. They would peek their head around the bedroom doorway, whether the door remained on it’s hinges or not.

With an amused chuckle, they would leave their neighbour to sleep off their over-indulgence. Flopped awkwardly on their bed and snoring peacefully, the drunkard would later have to figure out for themselves what they needed the carpenter to fix, and if the tailor would have any trade from mending rips in their clothes.

After all, everyone in Ferria knew not to go out after dark.

Leave a Reply